For many agencies, digital compliance with Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 is an ongoing process. Especially this year, with updates in January 2018 to formally include the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

The revised requirements are giving many government service providers incentive to educate themselves on accessibility, as well as review and refresh formally noncompliant platforms and websites.

With this in mind, we did some education of our own, in the form of a company Project Spotlight review. Developer Caroline Casals presented the background on accessibility, and some ways we can better meet the compliance needs of our clients.

Many hands

Casals underlined her belief that accessibility is a team effort, with all members of a project team doing their part, from PMs, to designers, devs, content managers, and QA. Many hands makes light work, as the saying goes. If each member of the team does their bit, accessibility compliance become less of a burden.

“When you say accessibility, everyone thinks it’s just color contrast and font size,” says Casals. “But it’s not just about design. The thread of accessibility compliance runs through every phase of a piece of software. Developers need to think about properly formatted controls and pages. QA needs to incorporate compliance into test suites. Project Managers need to sort issues by levels of importance and make sure everyone does their part to meet requirements. It’s not one person’s problem.”

Background on Section 508

“The power of the Web is in its universality,” said Tim Berners-Lee. “Access by everyone regardless of disability is an essential aspect.”

According to statistics, 18.7 percent of Americans have a disability, and 54 percent of adults living with a disability go online.

Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 is a federal law mandating that electronic and information technology developed or used by the federal government be accessible to people with physical, sensory, or cognitive disabilities. Any state or local agency that accepts federal funding must have digital services that are Section 508 compliant.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

The January 18 updates to Section 508 give fewer exemptions for hardware and software and additional interoperability requirements for braille displays and screen magnification software. They also now require use of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) from the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C).

The WCAG, produced by the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), provide guidance on how to be 508 compliant. The recommendations include how to make text easier to read for users of screen readers and assistive technology, and guidelines for descriptive tags on visual content, such as videos and images, to aid users with low or limited vision, with priority levels of 1, 2 or 3:

- A – a basic requirement for most groups to be able to use Web documents

- AA – will remove significant barriers to accessing Web documents

- AAA – will improve access to Web documents

An updated edition, WCAG 2.1, was released this year in January 2018.

POUR principles

To aid in the process of developing WCAG compliant digital hardware and software, the W3C guidelines define the four principles of web accessibility with the acronym POUR. Accessible applications should be Perceivable, Operable, Understandable, and Robust.

1) Perceivable

- User must be able to see or hear content, with text alternatives that explain the purpose of audio, video, and images, and attention must be paid to color, contrast, and text size

- In other words, all users are able to have the same experience on a site

2) Operable

- Navigation must be easy to understand, including breadcrumbs, headings, menus, and search, and keyboard commands must work for people who can’t use a mouse

- In other words, all site elements and controls are usable

3) Understandable

- Language must be clear and usable and site behavior must be predictable with clear page titles and headings

- In other words, the content is easy to follow and use

4) Robust

- HTML should be validated to allow for cross browser and platform compatibility, and should work with assistive technologies

- In other words, all content can be accessed by a range of technologies

Our examples

Some of the most common issues for WCAG compliance concern link treatment, button element contrast, and making forms accessible to screen readers. Like photos, examples are worth a thousand words. Casals took at look at one of her projects to find instances where simple changes were needed to meet compliance. Using testing software she found the following items:

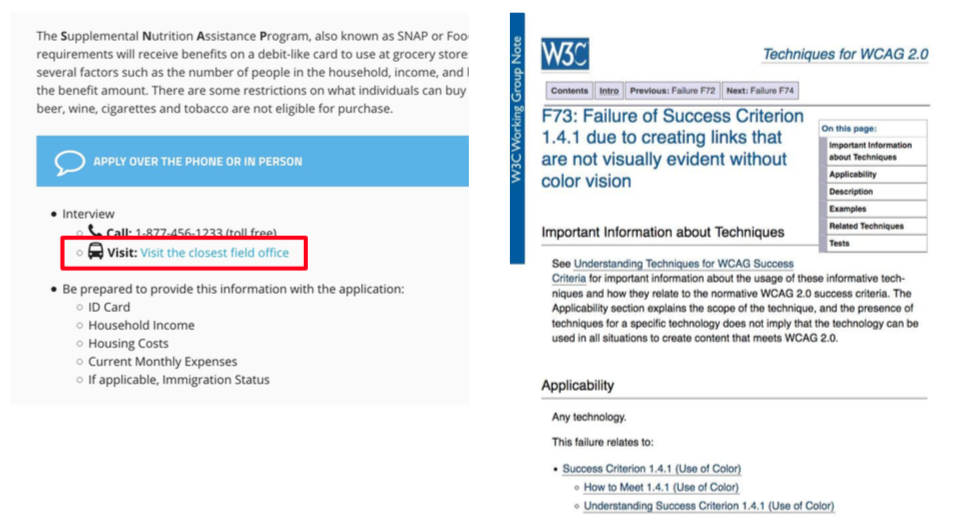

1) Links

F73: Failure of Success Criterion 1.4.1 Links that are not visually evident without color vision.

“The objective of this failure is to avoid situations in which people who cannot perceive color differences cannot identify links (when people with color vision can identify links). Link underlines or some other non-color visual distinction are required (when the links are discernible to those with color vision). While some links may be visually evident from page design and context, such as navigational links, links within text are often visually understood only from their own display attributes. Removing the underline and leaving only the color difference for such links would be a failure because there would be no other visual indication (besides color) that it is a link.”

2 ) Images

1.4.3 Contrast (Minimum): The visual presentation of text and images of text has a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1.

“The intent of this Success Criterion is to provide enough contrast between text and its background so that it can be read by people with moderately low vision (who do not use contrast-enhancing assistive technology). For people without color deficiencies, hue and saturation have minimal or no effect on legibility as assessed by reading performance (Knoblauch et al., 1991). Color deficiencies can affect luminance contrast somewhat. Therefore, in the recommendation, the contrast is calculated in such a way that color is not a key factor so that people who have a color vision deficit will also have adequate contrast between the text and the background.

3) Forms

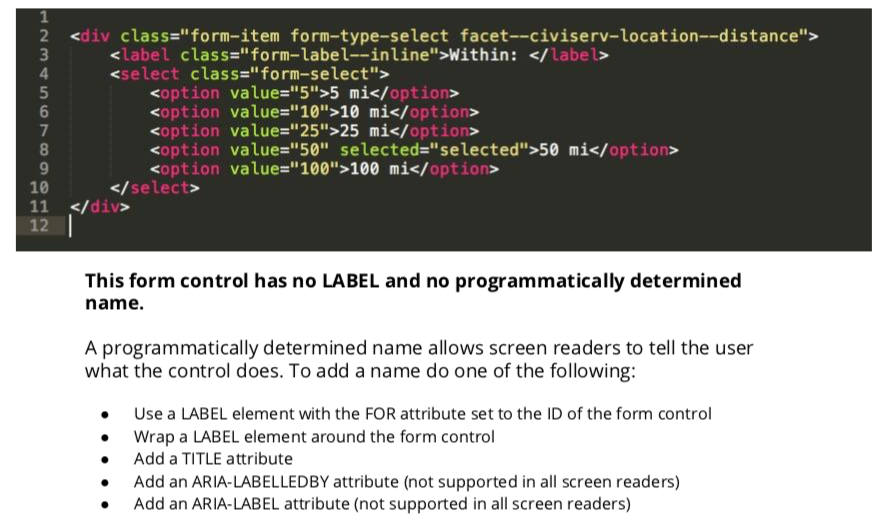

H44: Using label elements to associate text labels with form controls.

“The objective of this technique is to use the label element to explicitly associate a form control with a label. A label is attached to a specific form control through the use of the for attribute. The value of the for attribute must be the same as the value of the id attribute of the form control. The id attribute may have the same value as the name attribute, but both must be provided, and the id must be unique in the Web page.”

Label elements should be attached to the controls they label. This form control has no LABEL and no programmatically determined name.

A programmatically determined name allows screen readers to tell the user what the control does. To add a name, do one of the following:

- Use a LABEL element with the FOR attribute set to the ID of the form control

- Wrap a LABEL element around the form control

- Add a TITLE attribute

- Include an ARIA-LABELLEDBY attribute (not supported in all screen readers)

- Add an ARIA-LABEL attribute (not supported in all screen readers)

In summary

As we can see from the above examples, simple things make a big difference, and not just in terms of meeting requirements, but for the 50 million Americans with disabilities.

While there are many ways to meet compliance, a team approach helps. Each member of a team can focus on different aspects of accessibility.

Finally, it’s important to remember that automated testing alone is not always sufficient to meet compliance, as detailed in Why Manual Accessibility Testing Matters. Manual review needs to go hand in hand with automated testing to assure requirements are being met.

Learn more

- Refresh Toolkit – resources designed to help transition to the Revised 508 Standards in effect as of January 18, 2018

- WCAG 2.1 – Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1

- Let us know if we can help with your accessibility questions or concerns