“When you or I have conversations with people, the interactions don’t just consist of words. We shrug, point, roll our eyes,” says Jon Bloom, a conversation designer at Google. “Conversations with digital assistants should be just as dynamic. We’re reaching the point where cutting-edge technologies can provide users with the flexibility to communicate as naturally with machines as they would with a friend.”

Bloom’s work at Google consists of exactly that, making conversations with digital assistants as much like talking to humans as possible. The key, he says, is in understanding the nature of misalignments, or instances where the meaning of a request or question is misunderstood, and applying grounding strategies that help to clarify the misunderstanding and correct it.

With 20 years of experience in the industry, Bloom brings a wealth of context to the importance of conversation design. To support the recent work we’ve been doing on chatbots, we asked Bloom about the tricks conversation designers bring to the trade.

What do conversation designers know about conversation that the average person does not?

Fair question! It’s certainly the case that nearly everyone carries on conversations. We are all experts at it. As a species, we’ve been speaking for millennia, and as individuals, we’ve been detecting grammatical rhythms since the womb. The challenge is that because we are all so good at carrying on conversations, the subtleties become invisible to us. To use a single example of this invisibility: The average pause between conversational turns is about 200 milliseconds. Even subtle variations in the length of that pause can be meaningful. A longer pause could communicate distaste in what was just heard or a lack of certainty in the upcoming response. A response that is quicker than 200 milliseconds could imply great certainty but could also be considered rude in some cultures.

As conversation designers, our job is to sweat these details. All people who carry on conversations are experts at these skills, but the skills are invisible most of the time. I can ride a bike, but don’t ask me how I do it! It’s the conversation designer’s job to understand how.

What drew you to a career in conversation design?

Originally, it was to make customer interactions with call centers more effective, efficient, and usable. Back in the 1990s, conversation design focused mostly on designing phone menus (that’s still a huge focus today, but back then that was the lion’s share of conversation design roles). Major improvements happened with the advent of speech recognition (ASR) technology, text-to-speech (TTS) technology, and dialog management (i.e. systems to manage conversational turn-taking), so designers were brought in to harness that power. Before then, these systems never referred to themselves in the first person.

With the new technology, they interacted as if they were beings with agency. For example, before the ’90s, a system might say, “That response was not understood.” Now they were saying, “Sorry, I didn’t understand.” Those changes were the work of conversation designers.

The creation of these new “characters” made for better experiences in many ways, but we also had to figure out new rules of engagement, like how to avoid setting expectations too high about what the systems could do, or misleading callers into thinking they were talking to an actual person.

What do you like most about your job?

There’s still a disconnect between how people talk to each other and how people need to talk to digital assistants to get things done. What I love about my job is identifying those differences and collaborating with my colleagues to tackle them one piece at a time. For example, imagine you call a maitre d’ at a restaurant and ask for “a reservation for seven” by which you mean 7pm. The maitre d’ replies, “Okay, seven people. For what time?” You could then say, “No, for 7pm,” and the miscommunication would be resolved. We can’t do things like that very well with digital assistants yet.

These kinds of subtle conversational strategies are what make human interaction beautiful, and it’s an exciting challenge to get the machines in our lives to behave just as subtly.

What has been the most significant shift in conversational interfaces during your 20-plus years in the business?

The first major one, which I mentioned above, was the collective decision to have these machines refer to themselves in the first person. But possibly the largest shift occurred in the early 2000s, when engineers figured out a way for these systems to handle the answers to open-ended questions. Designers were no longer constrained to presenting users with limited menus of three or four items at a time.

Instead of sending callers into a bottomless rabbit warren of menus and submenus, we could ask callers, “How can I help you today?” With a single response, the caller could get to their destination. Indirectly, that shift paved the way for the digital assistant of today, where a single utterance like, “Hey Google, play Massive Attack on Spotify,” gets a task done.

Of course, this path has not been smooth the whole way. We’ve learned over the years that in the context of phone systems, these open-ended questions can sometimes be daunting, because callers don’t know what they can and can’t say, so best practices have evolved to ensure these moments work. For example, you can mention to the caller some examples of what people can say, have a fallback menu if things don’t work, and if you have a good idea why someone is calling, start with a simple yes/no question first before falling back to the open-ended one.

Could you explain misalignment and grounding?

Sure, to clarify what “grounding” means, when people have conversations, we are always attempting to be at the same level of understanding about the world as the other person. And each thing we say in a conversation is an attempt to update the other person’s understanding so that we end up “on the same page.”

This process of constantly getting on the same page through language is called “grounding”. If you say “I saw Lisa today,” then we are both now privy to that information. Me saying, “Oh that’s great,” is a grounding strategy because it lets you know that we are in alignment.

Simple enough. But sometimes, a contribution doesn’t bring two people into alignment, and so other grounding strategies need to be employed.

There are many layers of a conversation, from the basic superficial audio signal down to the subtle intents hidden beneath what we say. Misalignments can occur at any one of these layers:

- I could speak to you and you don’t hear me.

- You could pick up that I’m talking but not know I’m talking to you versus someone else in the room.

- You could figure out I’m talking to you, but not catch the words.

- You could hear the words but not understand what one or more of the words mean.

- You could hear the words, know what they mean, but not be able to figure out what on earth I mean in saying them.

What’s an example of using a grounding strategy to deal with a misalignment?

All of the above examples require you to employ slightly different strategies to bring the conversation back on track. For example, if you didn’t hear the words I said to you, you might ask me to repeat what I said. But if you heard me but didn’t understand what I meant, I’m unlikely to solve the problem by simply repeating myself. I had a stats professor in grad school, and he had clearly been there too long and was out of patience. Whenever a student asked for clarification on a subject, he would pause and then simply repeat what he had just said. This professor’s decision to repeat instead of clarify was an example of applying the wrong grounding strategy, and the effect for the listener was rude!

With digital assistants, designers face the same challenge. How do we properly address misalignments so that we do the right thing and also avoid being annoying or rude? Designers of conversational interfaces need to prepare grounding strategies to address almost all of the misalignment types mentioned above.

For example, asking the person to repeat themself, asking them to confirm what they said, asking for clarification of something mentioned, etc. And the designer needs to consider how many clarifying questions to ask before becoming annoying. Consider if someone says to Google Assistant, “Hey Google, play After the Gold Rush”. We already have a major misalignment requiring clarification. Does the person mean the song or the album? Do they mean the original studio version or a live version? Neil Young’s version or Dolly Parton’s recent cover of the song? Ideally, we can make some confident assumptions about what they mean based on their previous requests, or on general popularity of various versions. We can’t rely only on that or we might confidently make wrong assumptions about what to do, so we might ask things like, “Do you want the song or the album?”

Google is still perfecting these strategies, balancing intelligence (be smart and just take action) with humility (asking the user for help in doing the right thing). Last night, I asked my Assistant to play a song by Motorhead (don’t judge!), and it asked me if I wanted the version by Motorhead or Sepultura. That was pretty good!

Regarding your blog on The Rule of Three, are there exceptions to the recommendation to offer verbal and written options in groups of three?

Absolutely. Groupings of three are best when you absolutely have no choice but to present a menu of multiple options. But in a perfect world, you can provide better experiences than a menu, and the best interface is no interface at all.

If there’s a proactive way to address a user’s needs, so they don’t need to engage with you, that’s the ideal for both the user and you. Imagine a pizza delivery app that tells the user how far away their delivery is so they never have to call and ask. Another way to think of that is that the app has a non-existent menu with zero options.

If that’s not possible, then the next best option for the user is a situation where they have to engage with you, but you have a solid idea of their intention for engaging. In such a case, then you can respond with a single statement that’s likely to end the conversation. Imagine people calling their electric company during a power outage, and are greeted with a recording providing an estimate of when the outage will be cleared.

Third best, you have slightly less confidence about the reason for the user’s engagement, but there’s one possible reason that is most likely. Imagine that same electric company getting a call from a customer not in an outage situation. They know that the most common call in that case is about billing questions. In that case, they can ask a simple yes/no question: “Are you calling with a question about your bill?” We can think of that as a menu with only one option. Only after all these strategies are exhausted should you be considering a menu. And once you’ve decided on a menu, then yes, three options is the way to go.

You also wrote, “a negative user experience that comes from poor design decisions is a microstressor like any other.” How do you minimize microstressors?

Just like with traditional visual interfaces, user experience research is key to uncovering microstressors in conversational interfaces before they occur in production. The only way that conversational interfaces are different during user testing is that you can’t rely on the “think aloud protocol” (i.e. asking participants to speak their thoughts as they complete a task) because thinking aloud will trigger a speech system! So we unfortunately have to rely more on participant recollections of experiences after a task is done. At Google, we also require a period of time where we internally use the new feature ourselves before it’s launched. Of course, we rarely represent the larger user population, so our comfort with the feature is not sufficient as a seal of approval. But if we experience micro (or macro) stressors using a new feature, we will be sure not to launch.

What new conversational technologies are you eagerly awaiting?

Call me boring, but I’m most excited about further integration of existing technologies and modalities into conversations with machines. When you or I have conversations with other people, the interactions don’t just consist of words. We shrug, point, roll our eyes, etc.

If you go into a cafe and ask if they have Wi-Fi, the barista might say, “Yes we do,” and point to a sign with the login credentials. The words, the pointing gesture, and the sign are all part of the response. Conversations with digital assistants should be just as dynamic.

I’m excited to see how Google Assistant takes advantage of Google Lens, gesture recognition, and other cutting-edge technologies to provide users with the flexibility to communicate as naturally as with machines as they would with a friend. That’s the dream!

Learn more

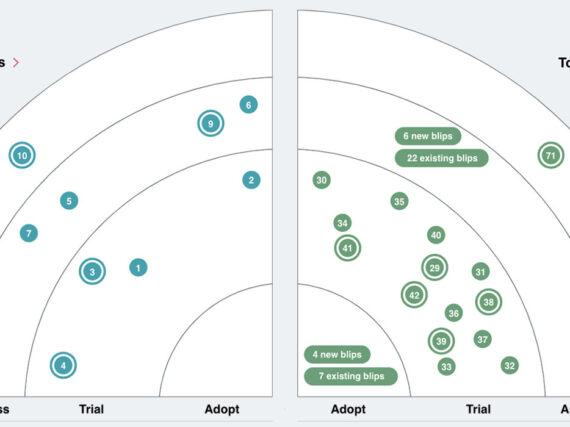

- Contact GovWebworks to learn more about conversation design for chatbots

- Work with our team developing chatbots for the public sector

Articles with Jon Bloom:

- The “Rule of Three” Also Works in Conversation Design, Google Design

- Conversation design and grounding strategies with Jon Bloom, VUX World

Videos with Jon Bloom:

- Navigating the Hurdles of Conversation Design, Amuse UX Conference

- Conversation design and grounding strategies with Jon Bloom, VUX World

Follow Jon Bloom on Twitter: